Featured products

-

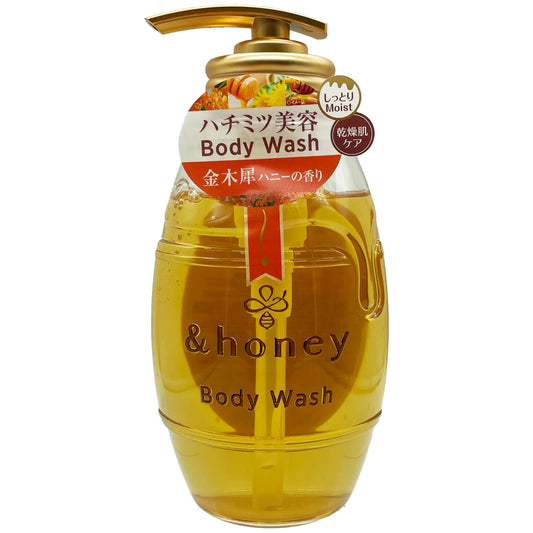

&honey Deep Moist Gel Body Wash Honey Fragrance 500ml

Regular price $16.99 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$18.99 USDSale price $16.99 USDSale -

&honey Deep Moist Hair Oil STEP 3.0 100ml

Regular price $22.99 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$24.99 USDSale price $22.99 USDSale -

&honey Deep Moist Shampoo Step 1.0 440ml

Regular price $23.99 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$25.99 USDSale price $23.99 USDSale -

&honey Deep Moist Treatment Step 2.0 445g

Regular price $23.99 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$25.99 USDSale price $23.99 USDSale -

&honey Melty Moist Gel Body Wash Rose Honey Fragrance 500ml

Regular price $16.99 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$18.99 USDSale price $16.99 USDSale -

Acecook Super Big Ramen Cup Soy Sauce Flavor 3.63 oz

Regular price $2.99 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Acecook Super Big Ramen Cup Tonkotsu Flavor 3.66 oz

Regular price $2.99 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

additional fee rule

Regular price From $0.02 USDRegular priceUnit price / per